This has not been proofed the way I like to proofread but I am practicing letting go of my perfectionism (my Virgo moon is my chart ruler lolsob) and sending it out anyway. The link roundups this month are free because it’s Pride Month and since my content is queer year-round, that feels like one thing I can do to mark the occasion for my free subscribers. Thank you for being here! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription if you like what you read! Paid subscriptions allow me to dedicate more time to this newsletter. It’s not just the time I spend writing, but the time I spend planning, researching, and reporting that is supported by upgrading.

why I hate the “this is for all the little girls” messaging

If you’re new to women’s sports, you may be noticing how concerned the coverage and marketing of these leagues are with the next generation of players, the “little girls” who are watching and being inspired by their favorite athletes. This coverage is so focused on the future of the game and the players who will come next that it almost seems to forget that there are players here now, currently, and also that there were players here before the present ones.

Not only that, it reinforces cultural ideas that what women do only has value if it’s in service of the next generation, or that it’s their job to nurture children in all areas of their lives.

The PWHL, particularly, leaned in hard to this messaging in its inaugural season, making it almost the entire focus of the league’s public image.

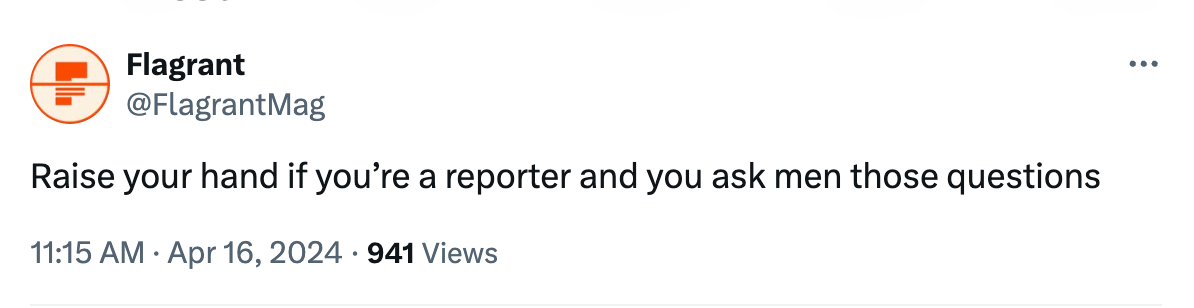

We saw lots of this at the WNBA Draft, as well. “No shade (also shade though) but the number of times the draftees were asked what their ‘message for young girls is’ or ‘how does it feel to inspire a younger generation’ last night was really something,” Flagrant Magazine said on X.

It extends to all pockets of women’s sports, too, not just the professional realm. For National Girls and Women in Sport Day earlier this year, Ole Miss Athletics launched their “Do It For Her” campaign, which included “a meet and greet with all of its women's teams and youth in the community to promote what the next generation can aspire to achieve,” according to a press release. Meanwhile, Tufts University spent their National Girls and Women in Sport Day “empowering the next generation of female athletes.”

Ironically, the Victorian-era arguments for keeping women out of sports were just the other side of this same coin: there was worry that vigorous physical activity, like athletics, would damage women’s reproductive organs and risk their ability to bear children. Essentially, the reason women should not participate sports was in service to the next generation, as well, to ensure they could have them and raise them.

Women are tasked with nurturing children and society reinforces the idea that their lives should be dedicated to that job—whether by not participating in sports so they can birth them or by playing sports so they can inspire them, whether they stay at home to raise them or enter the workforce to provide for them. Everything they do has to be in service of the next generation, in a way we do not ask of men. It’s why there is so much stigma against women who are not mothers, especially those who are childfree by choice.

We let male athletes aspire to athletic greatness and achievement simply for the glory of it or for the joy of it. When do women get to have the ambition for themselves, to play sports simply because they want to? When do we stop asking them to “do it for her [insert photo of little girl in the stands]” and let them do it for themselves, simply because they want to be great, to push themselves to their limits, and to achieve something?

“Sometimes I think we want little girls to dream but we don’t really want women to realize them,” Cassidy Lichtman, the Director of Volleyball at Athletes Unlimited, said on X recently. “Because the underlying, internalized notion is that women shouldn’t really have ambition, shouldn’t seek out the spotlight, shouldn’t put themselves first. And so even as we achieve greatness our greatness is measured by how we serve others.”

As women’s leagues have tried to build audiences, the focus on games being “family friendly” existed in a way that men’s leagues never required. In the 1970s, the teams of the National Women’s Football League hoped that marketing themselves as “family entertainment” would help them tap into fanbases that perhaps avoided going to games for the local men’s teams.

“The college football game atmosphere [at Ohio State University] was often filled with unruly male fans spewing obscenities, alcohol and raucous crowds,” Lyndsey D’Arcangelo and I wrote at Sports Illustrated, in a story excerpted in part from our book, Hail Mary. “At a [Columbus] Pacesetters game, many women and children joined their male family members in filling the stands to cheer on their friends, sisters, mothers and local athletic heroes.

“But billing themselves as ‘family-friendly’ meant that there was a part of themselves they had to keep under wraps: Many of the women who played for the Pacesetters were gay. They frequented Columbus lesbian bars like Summit Station and Mel’s, and a lot of players discovered the team through word-of-mouth there. In cities like Dallas, the local women’s bars bought ad space in the game programs of their NWFL team—the Shamrocks. The Pacesetters felt that wasn’t an option for them.”

In 2009, the WNBA’s Washington Mystics came under fire for their reasoning for not including a Kiss Cam feature at games. “We got a lot of kids here,” managing partner Sheila Johnson told Washington Post columnist Mike Wise at the time. “We just don’t find it appropriate.”

Now, of course, Pride Games are a huge part of WNBA culture—as well as most other pro women’s leagues, including the NWSL and PWHL. But even those are often framed as representation mattering for the little queer girls out there who can see people like them on the field. And while representation is important, Pride games are about more than providing inspiration for the fans. Pride games are also about queer athletes reclaiming the court or the ice or the pitch, about rightfully taking up visible space in the leagues that they have always been a part of and helped to build. Women’s sports culture is and always has been queer and Pride games are as much about asserting that fact as they are about vague gestures towards “inclusivity” and limp claims that “love is love.”

Women being able to claim something simply because they want it should be enough. They should be entitled to that right but we live in a culture that fears women’s desire, stifles it, asks them to shroud that desire in other things like building the game for the next generation or becoming an inspirational narrative in the making of “herstory.”

Let women want things. Let women achieve things. Watching women be successful for self-fulfilling reasons is perhaps even more inspirational to the little girls who are watching at home—it teaches them that they, too, can take ownership of their own lives and follow their own desire, creating a life that values what they can do for themselves and not just for what they provide for others.

Sports links for your Sunday

Earlier this week, I wrote about the controversy plaguing the PWHL after PWHL Minnesota drafted Britta Curl, a player who has expressed transphobic and homophobic views on social media. Shortly after that piece was published, the PWHL put out a fairly vague “inclusion statement” and Curl posted an “apology” on her social media.

For folks on Dijonalyssa watch, after Nalyssa showed up to DiJonai’s game, DiJonai showed up to hers the following night, Nalyssa filmed a TikTok with DiJonai’s dog, and has started campaigning for DiJonai for Defensive Player of the Year.

PWHL Ottawa goaltender Emerance Maschmeyer wrote a lovely piece for Hockey Canada about coming out and her life with partner, fellow hockey player Geneviève Lacasse: “There were hesitations in coming out publicly, but it didn’t really have anything to do with our sexuality. It had everything to do with the fact that both of us were still active with the National Women’s Team, and we didn’t want our news to be about our relationship or our sexuality. We wanted it to be about hockey and our performance… As someone who’s in a same-sex relationship, I know that at times I can still be a little timid or discouraged to be my true self, but for those in our community, I encourage you to be as courageous as you can. Be your true self. If you come into a conversation and lead with your authentic self, it will start changing minds slowly. One person at a time.”

This video of Sha’Carri Richardson and Cardi B is everything I’ve ever wanted.

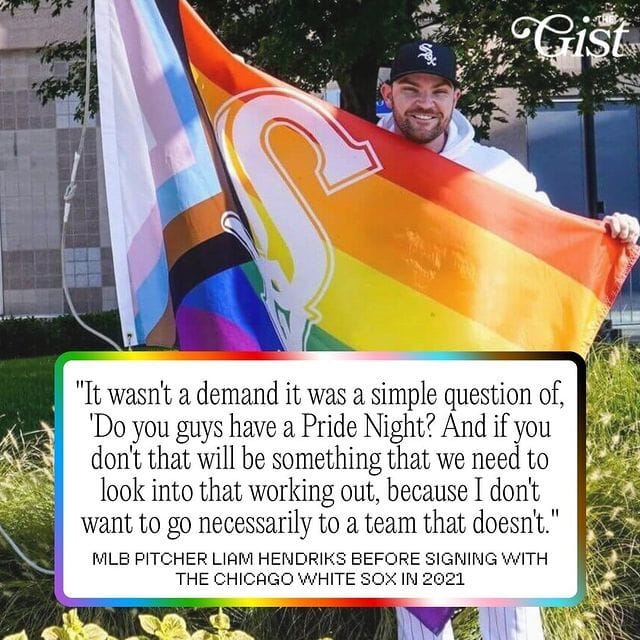

MLB pitcher Liam Hendriks, an ally:

PWHL Montreal teammates and fiancés, Laura Stacey and Marie-Philip Poulin, had a bridal shower and made the viral meme of a confused man wondering where their boyfriends were into t-shirts.

Love this video about The Armpits, a lesbian soccer team in Australia in the 1970s.

Quinn Rhodes (a newsletter subscriber! hi, Quinn!) interviewed actor Devery Jacobs about their role as a queer, Indigenous cheerleader in the new film Backspot: “As an athlete, as a queer person, I don't think anybody was looking at me and saying ‘queer cheerleader,’ but it's so much a part of me and the story that I wanted to tell.”

This short documentary about Ellie the Elephant, the New York Liberty’s viral mascot, is worth your time.

Megan Thee Stallion attended a Houston Dash game.

In the crossover I didn’t know I needed, Aubrey Plaza stars in the Olympic promo video for the U.S. women’s basketball team (turns out Plaza ia a huge basketball fan and plays in women’s pickup leagues!)