Thanks for being here! I am a full-time freelance sports writer. Paid subscriptions to this newsletter allow me to dedicate more time to this work, including hiring an editor to help me with posts like this one.

Paid subscribers also have access to a Discord server where we chat queer women’s sports, as well as events like our monthly book club. You can upgrade here:

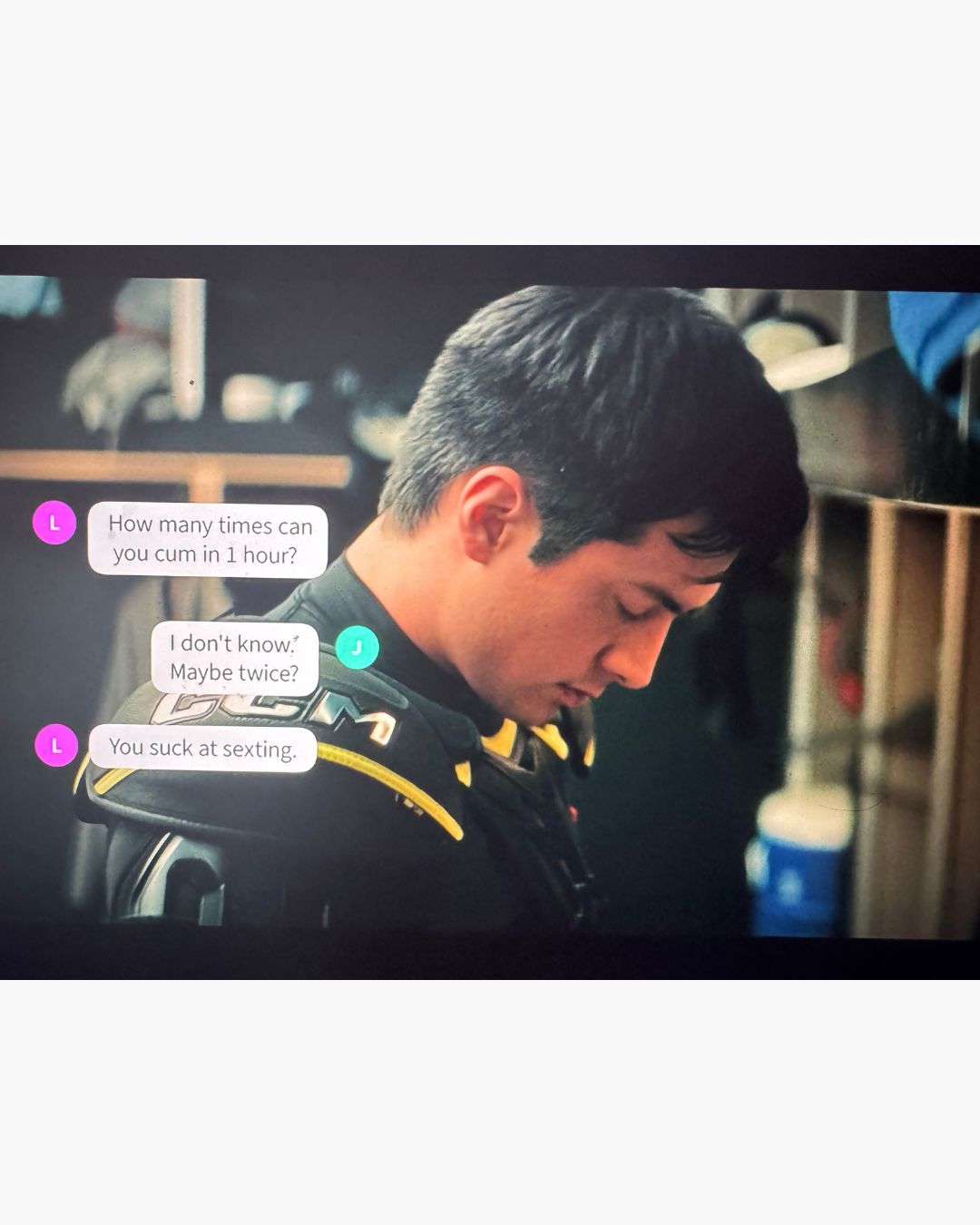

Shane Hollander is autistic. Neither the show Heated Rivalry nor the Rachel Reid book of the same name explicitly say so, but the clues are there: Shane’s particularity about his clothing and food, his flat affect that masks his internal emotional state, how literally he interprets everything that's said to him, how much the sexual power exchange between him and Ilya appeals due to his enjoyment of direct communication and clear expectations.

Reid has confirmed that Shane was written as autistic, and actor Hudson Williams said that he plays the character as such. “Sometimes autism’s portrayed in movies with quirky head movements, weird blinks, and weird inflections,” Williams said in an interview with Glamour. “And it’s like, Okay…? That is sometimes truthful but that’s always the reach. That’s always the way it’s expressed.

“Sometimes it is flat affect. It’s just being immobile in your seat and taking 10 seconds to move your hand to do something because you don’t know what this movement looks like or means.”

I agree with writer Sarah Kurchuck, who writes at TIME that Shane’s character is a step in the right direction for on-screen autistic representation. However, much of the discussion I’ve seen about Shane’s autism treats him as an elite hockey player who just happens to be autistic, and I'd like to push that observation further. I would argue that Shane’s autistic traits are integral to his success on the ice, as they are for many elite athletes who share them.

As I write this, I am not diagnosing anyone as autistic; that is not something I’m qualified to do. But as an autistic person who also has a master’s degree in mental health counseling, I am very familiar with what traits are highly correlated with autism. So many athletes possess those traits, and they are one of the biggest reasons why they excel at their sports.

I think about videos I’ve seen of NFL quarterbacks, like Kirk Cousins showing off his “computation notebooks,” in which he writes down his entire week, or Tom Brady watching 4-5 hours of tape per day, or Joe Burrow info-dumping about fossils to a water girl at practice, or literally anything from the Aaron Rodgers documentary. I think about the way baseball pitchers describe their routines in minute detail. The way these athletes are often described as “intense” or “obsessive.” Williams has even said he based his portrayal of Shane on a combination of his own autistic father and NHL great Sidney Crosby, who is known for his superstitions and idiosyncrasies.

Autistic people thrive on routine and predictable rules and expectations. They have special interests that they hyperfocus on to a nearly obsessive degree. They have great pattern recognition. Think of the (now outdated) stereotype of the autistic savant — in other words, people who are incredible talents at highly-specific skills. This description fits so many elite athletes, who feel safety and peace in practice schedules, gameday routines, and social scripts they learn in locker rooms.

Whether these athletes meet the diagnostic criteria for autism, it’s clear that possessing certain traits commonly seen in autistic people can translate to athletic success. (My dad, who is undiagnosed and likely where I get my autism from, played baseball at a high level, golfs at a nearly pro level, and has run a tennis academy my whole life). In popular media, autistic people are usually either Love on the Spectrum-coded — i.e., they are infantilized and assumed to be unable to live independent lives — or in the case of characters like Temperance Brennan on Bones or Sheldon on The Big Bang Theory, portrayed as smart and capable, but unathletic and uncoordinated.

The character of Shane Hollander eschews those tropes. So many autistic-coded characters are just that—written with autistic traits, but never confirmed to be autistic by writers or actors. Reid says that Shane isn’t labeled as autistic in the series not because she wanted to avoid it, but because she didn’t feel like it was something Shane would have known about himself.

NBA veteran Tony Snell went public with his autism diagnosis last year, after learning about it following his son's diagnosis. He also spoke about the stigma that follows autistic people, and why going undiagnosed as a child likely helped his athletic career. “I don’t think I'd have been in the NBA if I was diagnosed with autism because back then they’d probably put a limit or cap on my abilities," Snell told the TODAY Show.

And when footballer Lucy Bronze opened up about her autism and ADHD diagnoses, she credited her neurodivergence with her success on the pitch, calling it her "superpower." "I don't know if I'd say I'm passionate [about football]—I'm obsessed,” Bronze told the BBC last year. “That's my autism, it's my hyper-focus on football.”

Both Snell and Bronze say they struggled to connect with kids and teammates growing up, but by being elite athletes, a lot of the quirks that others might have read as “weird” or “different” were easily ignored in sports settings. We learn that Shane is the same way from one of the opening lines of the Heated Rivalry show. “He may not be the most sociable, but this is the kid with the highest hockey IQ out there,” the fictional television commentators tell us less than two minutes into the first episode.

Shane Hollander getting heartthrob and bicon Ilya Rozanov to fall for his autistic rizz is also a great example that autistic people can be hot and talented and have really kinky sex. And while those of us in the community already know that, it’s nice to see reality reflected on-screen. It’s about time we see autistic representation in elite sports, because the two are much less incompatible than many people (including athletes) seem to think.

This newsletter was edited by Louis Bien.