Thanks for being here! I am a full-time freelance sports writer. Paid subscriptions to this newsletter allow me to dedicate more time to this work, including hiring an editor to help me with longer, more involved posts, like this one. This financial support will also help me shoulder the costs of my planned move to Beehiiv next month, which has been a long time coming.

Paid subscribers also have access to a Discord server where we chat queer women’s sports, as well as events like our monthly book club. You can upgrade here:

ballhalla is queer & the valkyries know it

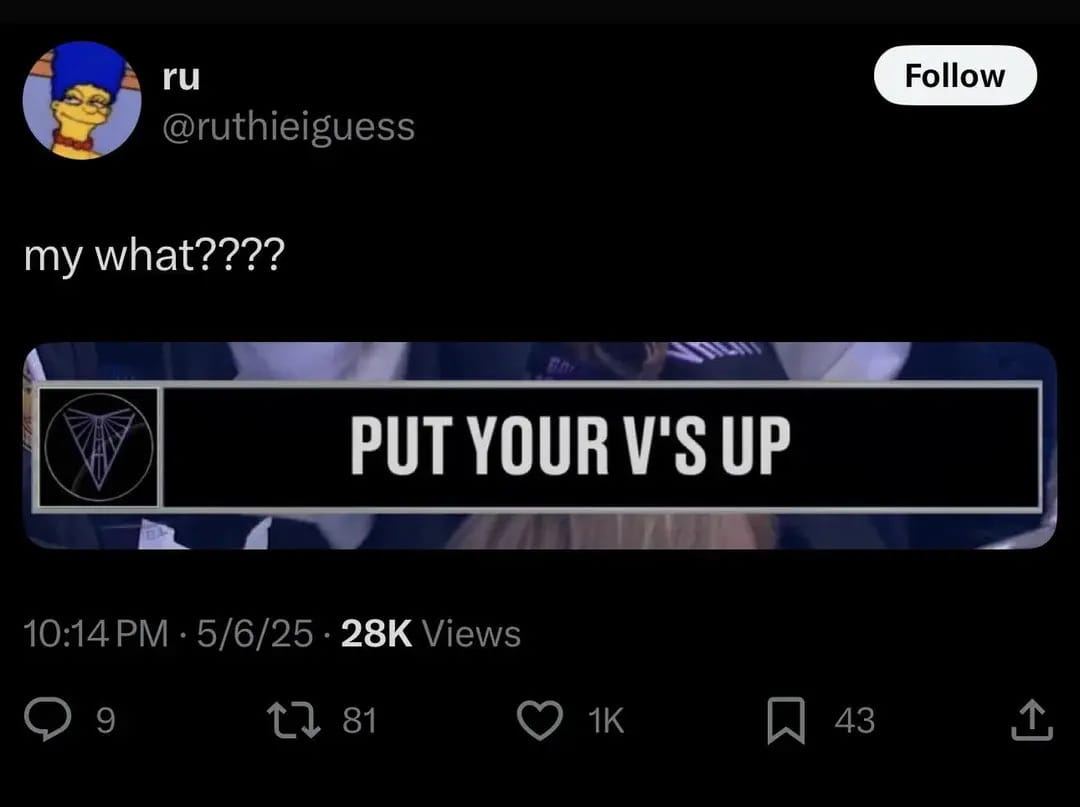

I’ve never been to Ballhalla, but I want to go. I can feel the energy of the place through the television screen, the packed stands of raucous fans fully behind a team that, before last month, didn’t even exist. The crowd, a sea of lavender, shows their allegiance by “putting their Vs up” in a gesture the sapphic community has quickly embraced as a queer double-entendre.

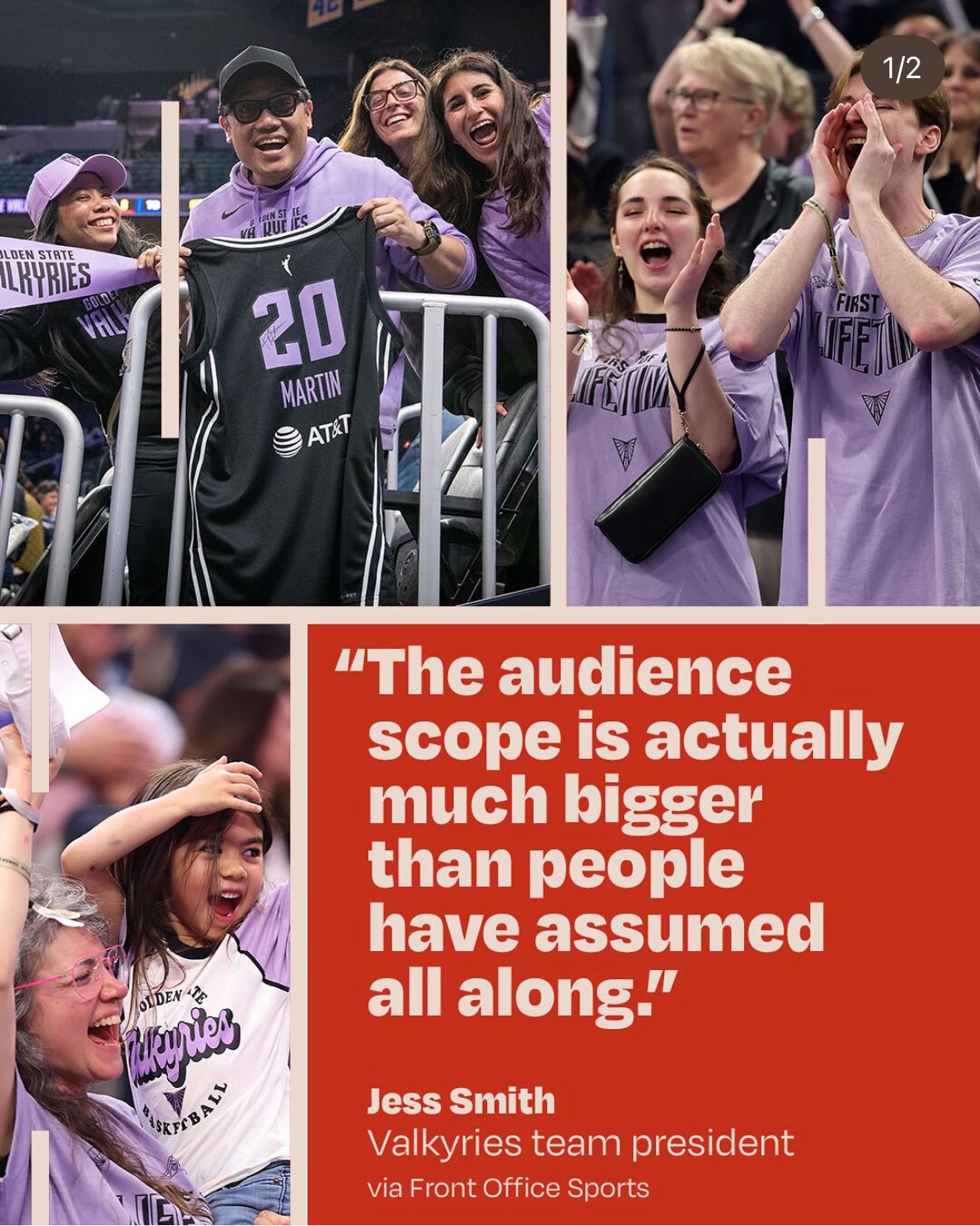

The Golden State Valkyries became the first team in league history to sell 10,000 season tickets, and every one of their first eight home games so far this season have been sellouts. Courtside seats for their debut game were priced as high as $3,900. Just this week, reported that they are the first pro women’s sports team to reach a $500 million valuation—meaning the newest WNBA team is already its most valuable.

Last Thursday night, Caitlin Clark and the Indiana Fever made their first journey to the Chase Center (aka Ballhalla) in San Francisco. At almost every other arena they play in—except maybe Barclays Center—locals spend hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars buying up all the tickets so they can be part of the “Caitlin Clark effect” in real time. Many of these new fans, who couldn’t name a single player on their hometown team, flock to watch the player who has been deemed the savior of women’s basketball. So much so that the Fever sell shirts that say, “Every game is a home game.”

When the Fever arrived, Ballhalla replied, emphatically, “Not here, it’s not.” For perhaps the first time, this Fever team, and Clark specifically, faced a crowd that was rooting firmly against them, and they appeared rattled. The Valkyries were able to hold Clark to 3-14 shooting from the floor, and 0-7 from beyond the arc. They forced six turnovers from Clark alone. Former Fever player Temi Fágbénlé called the Valkyries “a team of sixth women” before leaving Golden State to play in EuroBasket. An expansion team made up of role players effectively shut the Fever down. Having a rabid crowd certainly helped. Even after a loss last night to the New York Liberty, in a game that came down to the final possession, Ballhalla gave their home team a standing ovation and applauded the effort on the court.

“You would think, when you’re in Chase Center, that the Valkyries have been playing there 10 years, in terms of energy and show out,” says Megan Doherty-Baker, a season ticket holder and one of the co-founders of the ValQueeries, a fan group for LGBTQ+ Valks fans. “For that to be happening this early in their inaugural season is amazing.”

That crowd is reflective of the city the Valkyries play in, of the athletes who make up the on-court product, and of the marginalized fans who have always been drawn to the WNBA as a place where they feel welcome. “As I was walking out of the first pre-season game, I can see visibly how many queers are here and that doesn't include how many I can’t visibly recognize,” Doherty-Baker told Out of Your League. “I wished there was a sign or a way for us to organize this infectious energy. In queer communities, we can often recognize each other and sometimes there is a vibe where we look at each other and walk the other way, but I wanted to bridge that gap because there is shared interest here that is really obvious.”

Doherty-Baker brought the idea of an LGBTQ+ fan group to her season ticket rep, who she says was incredibly enthusiastic. Doherty-Baker and her ValQueeries co-founders made a Google Form to gauge interest, which their account rep shared with her list of season ticket holders, as well. They got over 200 responses in less than a month and have already organized several meetups and watch parties for away games.

Fandom is a funny thing. Historically, it can take generations to build. But the Golden State Valkyries managed to build a dedicated, completely bought-in fanbase before the team ever took the court. “The fanbase feels lived in,” says , who writes the newsletter and was born and raised in Oakland. “The franchise is capturing a lot of what people in the Bay Area already care about.”

How did they do it? A combination of being in the right place at the right time, and knowing exactly who their audience is: Queers. And whether they can maintain the momentum and goodwill they have built will depend on how this fanbase relates to the looming reality of the franchise as a corporate entity.

tapping into nostalgia

The Golden State expansion team, the WNBA’s first since the Atlanta Dream in 2008, was announced in October 2023, following the Las Vegas Aces winning their second championship in two years. Historically, expansion teams take a while to catch on, and they’re not always successful. They also often struggle in their first season on the court.

The Valks have so far been the biggest outlier in WNBA history, notching the highest attendance for any team in its first season and becoming the fastest expansion team to five wins. They notched four wins in less than a month of existence, as many as the Dream recorded in their full inaugural season.

Success puts a lot of butts in the seats. But there was no way to have known that the Valkyries would be that good before the season started, when fans purchased their tickets. No offense to reigning champion Kayla Thornton, vet Tiffany Hayes who was coming off a Sixth Player of the Year win, or beloved fan favorite Kate Martin, but there was no Caitlin Clark- or Angel Reese-level draw on this Valks roster. In fact, there were a ton of international players that many WNBA fans had never even heard of.

So how do you sell a team that you think is going to lose a lot? Very intentionally.

Professional sports teams often take more than a decade to become financially profitable, according to economist , and their success is directly tied to how long they take to build a fandom. Simply telling people that your new team exists won't make them identify with it. You need to define what it means to root for, say, a New York Liberty vs. a Golden State Valkyrie. You need to spark emotional investment. College and national teams don’t have the same problem that pro sports teams do, which Berri explains “have built-in fan bases.”

“Consider the US Women’s National Soccer Team, which has millions of fans and viewers, but when Megan Rapinoe put on her [Reign FC] jersey and [took] the field as part of the National Women’s Soccer League, the fan base [didn’t] necessarily follow her," Lyndsey D’Arcangelo and I wrote in our book, Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League. "When you create an entity that never existed before and say, ‘This is the Chicago Bears’ or ‘This is the Dallas Bluebonnets,’ people don’t have any emotional attachment to that.”

In the absence of a local team, fans will buy into a sport like women’s basketball with a team that does exist. When a local team finally does move in, it can't undo preexisting allegiances overnight. For example, part of why I was a Red Sox fan before ever moving to Boston was because I’m from South Florida, and we didn’t have a team until 1993, when I was 9 years old. In lieu of a hometown team, I rooted for the team my grandfather loved (which also pissed off my Yankees fan father). Even after the Marlins won their first World Series in 1997, it took many years for me to adopt them as my own, and many South Floridians never have.

Joanna Schwartz, a sports marketing expert at Georgia College & State University, told Marketplace that, because expansion teams don’t have star players or built-in rivalries to promote, they have to lean into values and community. “[Women’s sports fans] really want to commit dollars and time into places and things that they believe are building a better tomorrow,” she said. “That's part of the trick for teams that are going to be below .500.”

Women’s basketball fandom runs deep in the Bay Area and Northern California, and the Valkyries have wisely tapped into it. The San Francisco Pioneers played in the Women’s Professional Basketball League (WBL), the first-ever pro league for women in the U.S., from 1979-1981. Oakland legend Anna Johnson played for the Pioneers, and was honored as a hometown hero at the team’s May 20th game against the Washington Mystics—the same night the team got its first franchise win.

The American Basketball League (ABL), the women's league in operation from 1996-1998, had a team in San Jose called the Lasers. Farther north, fans ride hard for the Stanford women’s basketball team. And farther north still, they already know what it's like to love and lose a WNBA team. The Sacramento Monarchs were one of the league's founding franchises in 1997, playing for 13 seasons and winning a championship in 2005, before dissolving in 2009.

“I’ve heard tales of caravans of lesbians driving up to Sacramento from the Bay,” Goldberg-Safir says. “I’ve watched Sacramento Monarchs fans running into each other [at Valkyries games] who hadn’t seen each other in decades. When I talk to someone and ask, ‘Why are you excited about the Valks?’ they often bring up the Monarchs or Stanford or Cal.”1

The Valkyries are also part of a growing pro women’s culture in the Bay. The National Women’s Soccer League expanded to the area last season with Bay FC. The teams are even running ticket deals when they share a game day, bussing fans from one game to the other.

“There’s a readiness, in terms of those of us who have been waiting for a long time for the W to arrive in the Bay Area,” Doherty-Baker says. “It was awesome when Bay FC showed up last year and they’re building a great fanbase. They’re based in San Jose, and for folks in the South Bay, that’s awesome. I think they, by extension, have contributed to a fanbase ready to receive the Valkyries.”

knowing their audience

The rollout of the Valkyries branding should be studied in marketing classes. I can’t think of a better example of knowing your audience and making sure that the identity of the team appeals to them.

I want to be clear that, when I talk about “the audience” for the WNBA, I am specifically referring to racially diverse queer folks with progressive—if not radical—politics. These are the fans who have been there since before the WNBA was popular, who have shown up even when no one else did. “The WNBA has never had to worry whether to rely on lesbians to kick down cash,” a 2001 article in the Willamette Weekly reads. “As with the American Basketball League, the now-defunct women's league, the demographic ‘that dare not speak its name’ has been there for the NBA's foray into the women's game.”

This is also a reflection of the players who make up the league. About 27% of the current athletes in the W are openly queer, and the league is over 60% Black and over 80% people of color. And don’t forget that the players helped flip the Senate blue in 2020, campaigning for Democrat Raphael Warnock to oust Sen. (and Atlanta Dream owner) Kelly Leoffler (R-GA).2

Even though a Sportico survey found that the WNBA’s fandom was truly bipartisan—a 50/50 split between Democrats and Republicans—it is perceived as being far more liberal. Another 2023 survey of sports fans revealed that 71% of them (and roughly the same percentage of LGBTQ+ sports fans, specifically) perceived the WNBA’s political ideology as a league as either “more liberal” or “somewhat liberal”— the highest ranking among the seven professional leagues included in the survey. In that same survey, 73% of LGBTQ+ sports fans said investments in diversity and inclusion, like Pride Nights, make existing fans feel more accepted by the league, and therefore welcome at games.

And while the massive growth of the league in the last few years has proven there is a larger audience for the sport than people once believed—the largest demographic gains in viewership last season occurred among young viewers, male viewers and white viewers—the core audience that has always been invested in these teams and players remains the same. According to the Wall Street Journal, even with these changing demographics, Black viewers “watch the WNBA in far greater proportion than their 13% overall share of the U.S. population,” making up 34% of the WNBA viewership of ESPN networks and 45% of ION’s WNBA audience.

The Valkyries managed to tip their hat to this core audience without alienating any new fans.

Let's start with the name. “Golden State” creates immediate identification with the Warriors, an NBA team with a massive fanbase (and shared ownership). “Valkyries” extends that shared identity as a specifically female analog to the “Warriors.” In Norse mythology, a Valkyrie is a female warrior who decides who will live and who will die in battle. Valkyries are said to bring the bravest warriors to Valhalla, which is like heaven or the afterlife for warriors — hence, “Ballhalla.”

You don’t need to know Norse mythology to know what a Valkyrie is—you just have to be a Marvel fan, because “Valkyrie” is also a character from the Marvel comics who is played in the Marvel Cinematic Universe by the very hot (and very queer) Tessa Thompson. In the comics, Valkyrie is queer (though in the MCU her queerness is much more subtextual than textual). Then there's the team’s colors: black, white, and lavender (excuse me, “Valkyrie Violet”). Lavender has a very strong connection to queer communities and queer resistance. As do violets, which are often considered explicitly sapphic.

Finally, in case you thought all those queer references were a coincidence, the Valkyries first promo video was voiced by none other than lesbian singer—and Oakland native—Kehlani. For an even deeper cut, Kehlani is a long-time women’s basketball fan who has been attending WNBA games for years. Her ex-girlfriend was a Graduate Assistant coach at UConn (which explains why Kehlani and Paige Bueckers sometimes comment on each other’s social media posts).

The local Valkyries broadcast team hired Layshia Clarendon as one of their studio analysts. Clarendon is a California native who played college basketball at the University of California, Berkeley, and was the first openly non-binary player in the WNBA. The Chase Center’s official Valks DJ is DJ LadyRyan who has been honored by the City of Oakland for her leadership in the LGBTQ+ music and arts community and who, according to a press release, “curates an extraordinary platform that celebrates and sustains the unwavering spirit and beauty of Oakland’s queer and trans-BIPOC communities.”

During the games, sapphic Valkyries fans immediately latched on to the in-game PA announcement to "put their Vs up" by spreading their index and middle fingers and raising them in the air. “Welcome to the world Sappho envisioned,” wrote one commenter on espnW’s TikTok about it. Other teams may do similar gestures — the Phoenix Mercury encourage their fans to cross their arms in an "X" to represent the "X-factor" they bring to the stands — but none can be read as innuendo. The team has declined to answer questions about the potential double-meaning of the “V,” but that hasn’t stopped queer fans from feeling welcomed by it.

“It was such a clever call to action to get us engaged throughout the games,” says Doherty-Baker. “I don't know who came up with that but it [feels like] a nod to the queer community, who is having fun with that playfulness and innuendo and feels seen, throwing their Vs up while we’re watching women’s basketball. It's tongue-in-cheek, and it’s fun.”

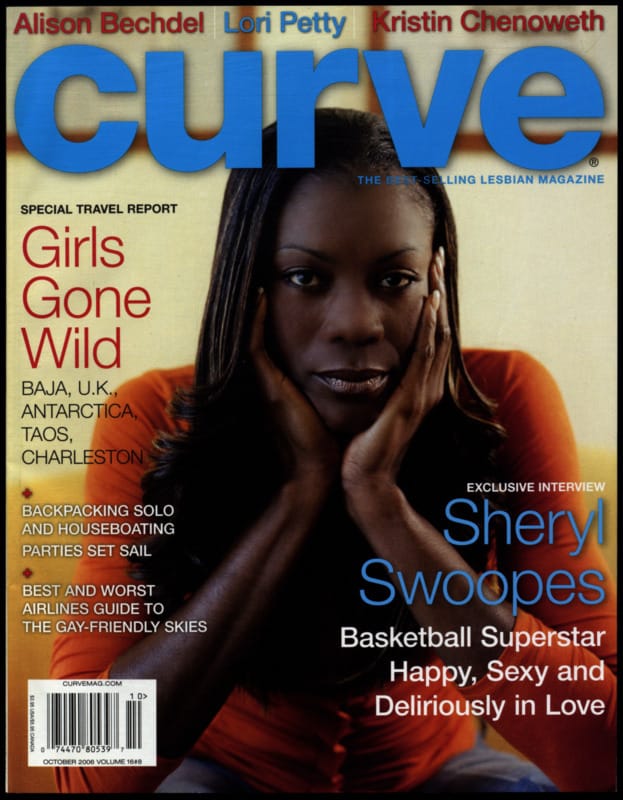

This all matters, of course, because it’s not just women’s basketball fans that tend to be heavily queer. The San Francisco Bay Area is deeply important to the story of queer activism and the queer and trans liberation movements, especially before the tech booms of the aughts gentrified the city. Three years before Stonewall, a group of trans people were hanging out at Compton’s Cafeteria in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco when the police arrived to arrest them for loitering. The customers fought back, throwing coffee cups, smashing dishes, and breaking windows. Curve magazine, the iconic lesbian magazine that was one of the first publications to feature queer athletes in women’s sports, was founded in San Francisco in 1990.

But the Valkyries are not just paying lip service to the larger community they're embedded in. The team also hired Natalie Nakese as their first head coach, making her the first Asian American head coach in WNBA history. As of 2022, 27% of Bay Area residents identified as Asian American or Pacific Islander (AAPI), second in the U.S. only to the Honolulu metro area. They also hired a Black woman as their General Manager in Ohemaa Nyanin. This is, again, a reflection of the demographics of the community where they play. Oakland, the largest city in the East Bay, was estimated to be 22% Black in 2022, and the two counties that comprise the East Bay Area, Alameda and Contra Costa, were estimated to be 11% and 10% Black, respectively.

Of course, the Valkyries' aren't exactly driven by altruism. “The Valkyries organization, thus far, is doing a great job capturing the feeling of a mission-driven product (women’s basketball + queer + diverse + lefty Bay Area culture)," Goldberg-Safir writes at rough notes. "But the franchise was still created with the ultimate goal of turning a profit.”

Capitalism has a way of poisoning everything it touches. The way teams like the Liberty have been gentrified as they’ve grown, pricing out local fans who have been there since the beginning, isn’t lost on even the most diehard Valks fans. While Valkyries President Jess Smith says she is intentional about ensuring that everyone can attend games—season tickets start at $25—Joe Lacob, majority owner of the Valkyries and Warriors, told the Wall Street Journal that his team plans to make more money than any other women’s sports team in the world. He also said that revenue in Year 1 is on pace to more than double one analyst’s estimate of $30 million.

“Being at a Valkyries game may highlight some of the best qualities about living in the Bay, but the Golden State franchise did not invent any of them,” Goldberg-Safir continues at rough notes. “Our participation is their currency. And the more comfortable we are, the more ‘just grateful to be here,’ the less likely a corporation will pay attention to our human hopes and dreams and desires and beliefs as anything other than white noise.”

This reality was evident during recent Valkyries games, one against the Seattle Storm on the Saturday of the nationwide “No Kings” protests, and the game against the Fever, which was played on Juneteenth. A season ticket holder named Donka told Out of Your League that their signs were confiscated by Chase Center security at both games. Donka, who lives in the East Bay, says they like to bring signs to Ballhalla as a form of community.

“It’s a way of speaking to each other in this place where we know has sold out 18,000 people, but we don't always get to interact with each other,” Donka says. “And so the witnessing of, ‘We're in this together, and we're sharing space, and we're behind these powerful professional women,’ there's this camaraderie that you experience. It's a way of connecting.”

While in the stands during the game against the Storm, Donka says they were approached by staff and told they couldn’t hold up their sign that read, “This is the only court we want… NO KINGS.” They said they were confused because two other “No Kings” themed signs had made it onto the Jumbotron. Then, at the following game against the Fever, they were disallowed from bringing in a sign that read, “Hey Caitlin, Black women paved the way for you!!! HAPPY JUNETEENTH,” and it was taken at the door with no clear explanation given.

“As we maintain Chase Center as an inclusive, safe and welcoming space for all who enter, and consistent with our venue policy, we maintain the right to deny signs that taunt players and/or are political in nature,” the Valkyries said in a statement to Out of Your League.

But Donka sees this position as a hypocritical one. “When you're going to have a Juneteenth event, or a Pride event, what is the watered down, pinkwashing of these events for?” they said. “Like, we're going to give this nod to it, but we're not actually going to allow the fullness of its potential to be present, and we're not actually going to truly lean into the meanings of these things.”

Another glaring example of Goldberg-Safir's warning was the disappointment from everyone I spoke with that the team didn’t end up playing in Oakland. “I feel especially for Oakland, they’ve been stripped of their sports teams,” says Doherty-Baker. “I was hoping the Valkyries would be based in Oakland because they have some of the best fans in the country and it's really sad. Even when you’re at Chase Center, they do a roll call and when they say ‘Oakland,’ it is uproarious in there. As much as they are based in San Francisco, Oakland is still deeply a part of that.”

appealing to the public

The Warriors' association with the Valkyries can't be ignored. Because the Warriors ownership is also behind the Valkyries, it does add a degree of legitimacy to the team in the eyes of men’s basketball fans and existing fans of the Warriors (this air of legitimacy was something the WNBA had banked on when they first launched, initially requiring each team to be a “sister team” to an NBA franchise).

I’m not one who thinks that having the backing of men, or men’s sports fandoms, is required for women's leagues to succeed. Nor do I believe that striving to be like men’s leagues should be the goal of the women’s game. As I’ve written before, I think a large part of the appeal of the WNBA is the fact that it isn’t like the MNBA.

But what Golden State does have is Stephen Curry, who has been a true ally to the women’s game throughout his career. His advocacy has been quiet, consistent, and respectful (unlike the way someone like Kobe Bryant used the women’s game as image rehabilitation after very credible rape accusations). Curry competed against Sabrina Ionescu in the 3-point competition at last year’s NBA All-Star Weekend and, regardless of what I think about the spectacle (spoiler: I wasn’t a fan), you can’t deny the fact that Stephen Curry respects the hell out of W athletes. To basketball fans in the Bay Area, it matters what Curry thinks, though it’s worth noting he hasn’t attended a game at Chase Center yet.

Members of the Warriors have been courtside at every Valks home game, including during their win over the Fever last Thursday night, when Brandin Podziemski could be seen trolling Clark with Curry’s famous “night night” celebration. In fact, Podziemski has been courtside at every home game, rocking a different player’s jersey each time.

And finally, the importance of real, consistent beat coverage cannot be overstated. Enter the San Francisco Chronicle, who hired Marisa Ingemi to launch the Valkyries beat. (Ingemi also originated the Seattle Kraken beat for the Seattle Times, so she is no stranger to covering a new expansion team). Ingemi is one of only a handful of beat writers with a mainstream publication in the WNBA, which not only keeps fans informed, but helps keep the game in the national conversation, as well as hold the franchise — ownership, management, coaches, players and personnel — accountable should they make missteps.

Historically, women’s sports have been shut out of traditional media. When it does get attention, the narrative typically focuses on supporting, uplifting and empowering women. And because so much of traditional journalism hasn’t existed in this space, content creators have stepped in, getting access and establishing platforms in a wide open market. As a result, a lot of women athletes aren’t used to journalists asking tough questions or providing critical coverage; they’re used to glorified fan accounts who are just happy to be getting access to their favorite teams and players.

Annie Costabile spoke about this phenomenon recently on the Sports Media with Richard Dietsch podcast. Costabile became perhaps the first traditional beat writer in WNBA history (or at least, modern WNBA history) in 2021 when the Chicago Sun-Times began sending her to cover every Chicago Sky game, home and away. “The biggest issue league-wide was, I would say, just lack of preparation,” Costabile said. “So there would just be issues that would come up that you wouldn't see in the NBA because the W just wasn't prepared for, again, this daily, critical, unbiased, [coverage]—like ‘we're not here to be your fan’ coverage.”

But if the WNBA ever hopes to be taken as seriously as its male counterpart, it needs to be willing to be covered like men’s sports. And that kind of day-in, day-out beat coverage from a journalist, who attends practices in addition to traveling to away games, is crucial. While more publications have added them over the last couple of years—including Chloe Peterson covering the Fever for the IndyStar, Madeline Kennedy covering the Liberty for the New York Post, and Kareem Copeland covering the Washington Mystics for The Washington Post, among others—there are still major gaps between the teams in how much they are covered. The Valkyries have had that since day one, which is something that came from Christina Kahrl, the sports editor at the Chronicle, seeing value in assigning a reporter to focus on the women’s teams in the area.

Golden State, for their part, have done a good job portraying themselves as a serious sports franchise worthy of the media scrutiny that comes with trying to win at the highest level. Their social media presence and branding has been strong, fierce, and mature. So much of women’s sports marketing focuses on tropes like “do it for the little girls watching at home,” which can feel infantilizing and demeaning to athletes who have worked their whole lives to compete at the top of their games. The Professional Women’s Hockey League is a great example of this kind of marketing that centers children and families in ways that are actually quite sexist (something else I’ve written about before).

“I think the Valks have made a massive effort to be seen as a pro sports team first and not a fun little kids’ event the way a lot of women’s sports sometimes hyper-focus on,” Ingemi told Out of Your League. “They present as competitive and athletic and not a novel like ‘girls can do anything’ vibe.”

Which doesn’t mean that families aren’t welcome at the games—of course they are. My friend wrote about taking her daughter to her first WNBA game at Ballhalla and what a wonderful experience it was. But the Valkyries want to appeal broadly, which is especially important to queer folks, who can feel excluded when teams focus solely on children and families.

Smith, the team’s President, told the Wall Street Journal that fans begged her to “make it cool,” which is something she’s clearly been able to do.

There's still work to be done. The Valkyries' mission is still putting butts in seats, and the history of sports is littered with franchises who sold out their fanbases for a buck.

Donka’s experiences of having their signs taken away has already impacted the way they feel about the franchise they were so excited to support. “We're giving our money to who? What do they actually stand for? And how are they disguising themselves by using women's sports to profit?” they wonder. “They want our money, but they don't want us, is almost what it is like. They don't want to allow us to speak who we are and what we all are about, and where this momentum is actually coming from.”

But all that said, it's refreshing and exciting to see a team make queerness part of its foundational DNA. I'm stunned by the promise of Ballahalla, and I'm not alone.

“I want the WNBA to learn from the Valkyries in this way,” Doherty-Baker says, referring to the way the franchise has embraced and seemingly centered its queer fans. “We've always been here and we've always been queer and we have incredible spending and political power. It’s nice to see a franchise acknowledging and honoring that in big and small ways.”

This story was edited by Louis Bien. Maya Safir-Goldberg contributed to reporting.